Celebrating Black History Month

February 17, 2021

In honor of Black History Month, we’re sharing stories of Black men and women who have had a major impact on the course of African American history. The individuals below—all of whom we’ve had the honor to include in our publications—represent examples of the significant contributions Black Americans have made to the fabric of U.S. history.

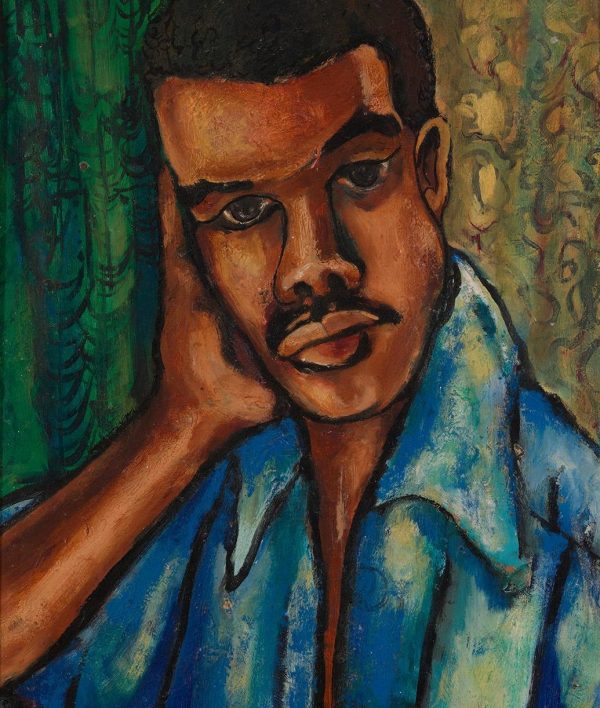

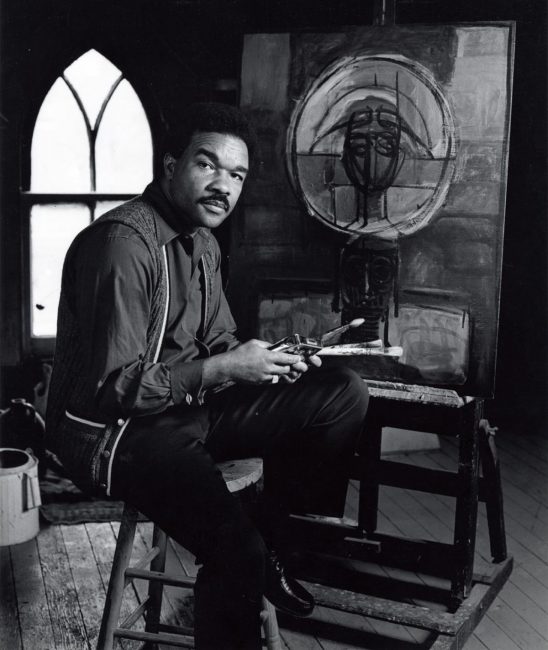

Above: David Driskell’s Self-Portrait, 1953

CURATING HISTORY

David Driskell (1931-2020) is highly regarded as an artist, scholar, and curator, and is cited as one of the world’s leading authorities on the subject of African American Art. A boundary-breaking artist who has been featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions, he is recognized for his sharp observations of American landscapes and the imagery of the African diaspora.

Driskell was equally well-known as a curator, art historian, and educator who created a durable public record of the long history of African American art. He was the recipient of ten honorary doctoral degrees, authored seven books on African American art, co-authored four others, and published more than forty catalogs from exhibitions he curated. Driskell was the recipient of many distinguished awards and is the namesake of the James A. Porter & David C. Driskell Book Award, given by the David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland. This award was created for the purpose of encouraging original research and scholarly writing on historical subjects pertaining to African American visual culture.

Recommended Reading: DAVID DRISKELL: ICONS OF NATURE AND HISTORY

All artworks are copyright © Estate of David C. Driskell,

courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

THE NEW GUARD

Corey Damen Jenkins’s design career began by canvassing subdivisions and new construction sites throughout Metro Detroit. “The phone wasn’t ringing. I then realized that I was being passive, reactive, and allowing life to happen to me. So, I decided to happen to my life…I found my first big clients by knocking on doors—literally, 779 of them—in the dead of winter in 2010.” Not long after, the Detroit-born designer—who describes his design style as “classically traditional with a youthful, hip, sexy edge”—was recruited by HGTV, where he won the network’s design competition series Showhouse Showdown. Since then the accolades keep growing: Jenkins has been inducted into Architectural Digest’s AD100, was named to ELLE Decor‘s prestigious A-List, and was awarded the New Trad Rising Star of Design Award by Traditional Home magazine. Jenkins was also invited to decorate a room in New York’s Kips Bay Decorator Show House, a design-world honor, and won the “Stars on the Rise” award from New York’s esteemed Decoration & Design Building.

During a keynote speech at the 2019 Black Interior Designers Network Conference, Jenkins spoke about the value of putting yourself out there and other ways people of color can continue to advance in the design industry. “As a child growing up, I didn’t see anyone that looked like me in magazines. But that’s changing. I think now it’s less about asking for a place at the table and more about pulling up a chair and just sitting down.”

Recommended Reading: DESIGN REMIX: A NEW SPIN ON TRADITIONAL ROOMS

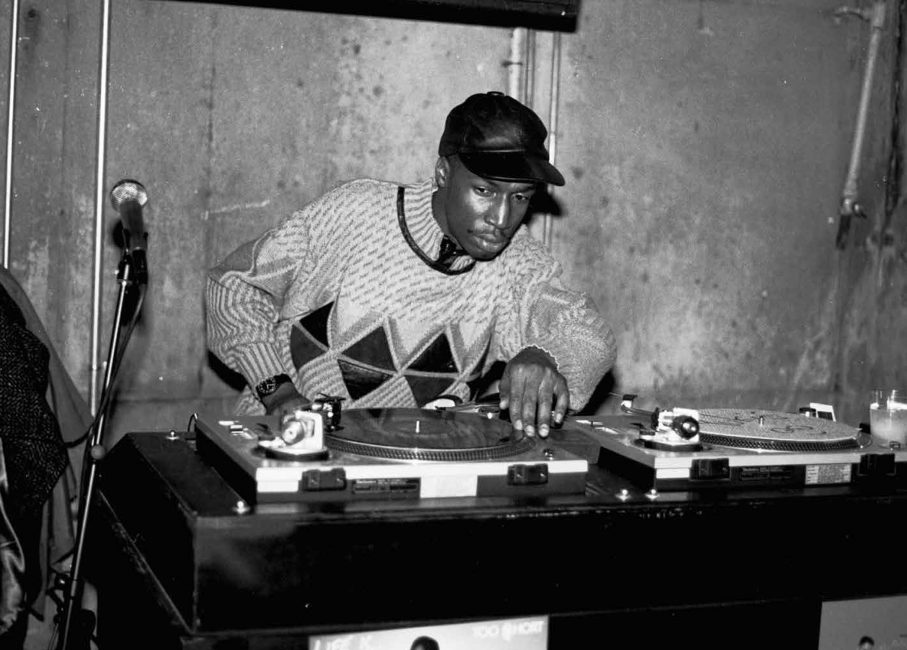

BREAKING GROUND and BEATS

Grandmaster Flash, born Joseph Saddler, is considered one of the pioneers of hip-hop DJing. As a teenager in the 1970’s, he developed a series of innovative techniques including “cutting” (moving between tracks exactly on the beat), “back-spinning” (manually turning records to repeat brief snippets of sound), and “phasing” (manipulating turntable speeds)—all techniques DJs use to this day. As part of the early New York DJ scene, Grandmaster Flash collaborated with rappers such as Kurtis Blow and Lovebug Starski, later forming his own group Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. Their hits included “The Message” and “White Lines (Don’t Do it)” (with vocals by Melle Mel), whose revolutionary lyrics exposed ghetto poverty, drugs, and violence in a way it had not been before. Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five were inducted into the Rock and Roll of Fame in 2007, becoming the first hip hop artists to be so honored.

Seen here: Grandmaster Flash photographed by Ernie Paniccioli

Recommended Reading: HIP-HOP AT THE END OF THE WORLD

RAISE A GLASS

Shannon Mustipher is one of New York City’s most sought-after authorities on rum and cane spirits. She also has the distinction of being the first Black American bartender to publish a cocktail recipe book in over a century (Rizzoli’s Tiki: Modern Tropical Cocktails, IACP 2020 winner in the Beer, Wine, & Spirits category). It was in her current position as Beverage Director of Glady’s—a Caribbean restaurant and bar in Crown Heights, Brooklyn—that Mustipher developed her much-lauded re-envisioning of Tiki after she was asked to create their rum-based bar menu. With creative twists on the old form, she created a new frontier of island-inspired drinks—one that’s conscious of the historical connection between the slave trade and rum, as well as the appropriation of Polynesian and Caribbean influences. “I think it’s possible to create cocktails and bar environments that appeal to the escapist vibes of a tropical environment—without needing to use symbols and iconography associated with a culture apart from your own. It’s a matter of using judgment and taste,” Mustipher said.

Mustipher is excited to see “more diversity and inclusivity” entering all levels of the bar space. “There are powerful and influential women, men, LGBTQ people, people of color, and every intersection making waves and huge contributions not only in bigger markets but at every point in between—hospitality has never felt more vibrant and hospitable, and there is no end in sight!” She further conveys this passion through Women Leading Rum, a cane spirit-centric professional organization she co-founded, and Women Who Tiki, a pop-up tropical cocktail series celebrating talented female bartenders.

Recommended Reading: TIKI: MODERN TROPICAL COCKTAILS

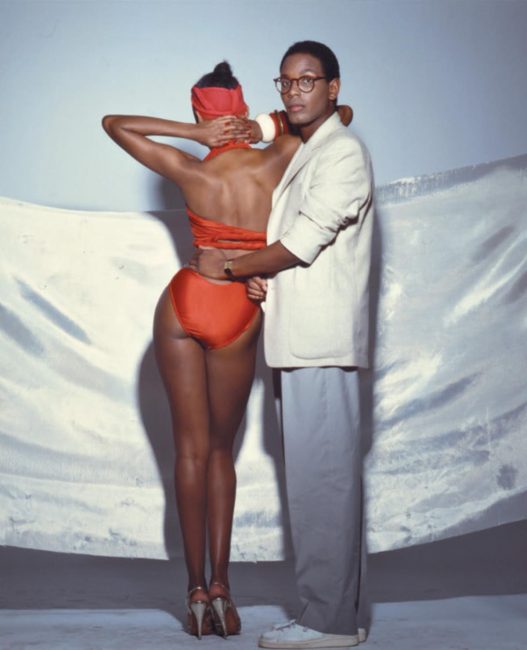

STREETWEAR PIONEER

Before Off-White, before Hood By Air, before Supreme, there was WilliWear. African-American fashion designer Willi Smith, a pioneer of streetwear and visionary collaborator, created inclusive and liberating fashion: “I don’t design clothes for the queen, but the people who wave at her as she goes by,” he said.

A rising star from the time he left Parsons, Smith went on to found WilliWear in 1976 and became one of the most successful designers of his era until his untimely death in 1987. He broke boundaries with his streetwear, or “street couture,” and trailblazed the collaborations between artists, performers, and designers commonplace today. Smith blurred the lines of gendered fashion in American sportswear with garments created for both his WilliWear Men’s and Women’s collections. He also played a key role in the democratization of fashion by keeping WilliWear at an affordable price-point, as well as by partnering with pattern companies Butterick and McCall’s to produce home sewing patterns of his collections. Smith’s gender-neutral collections for WilliWear can be seen as precursors for contemporary brands such as One DNA, Supreme, Off-White, Telfar, Vaquera, Eckhaus Latta, and Pyer Moss.

Recommended Reading: WILLI SMITH: STREET COUTURE

MAKER OF HISTORY

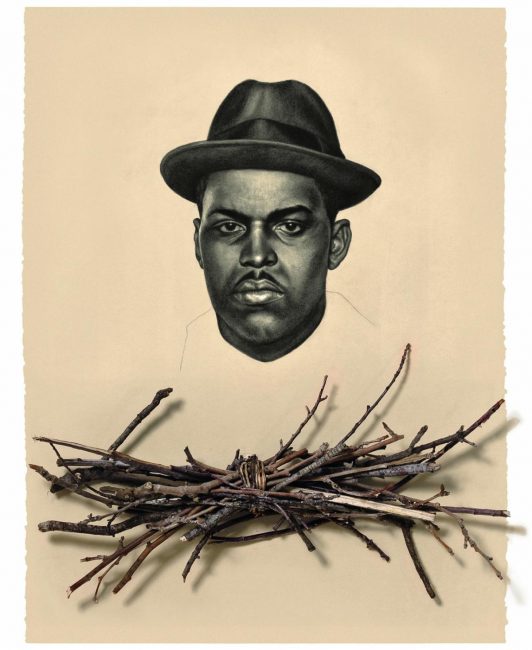

MacArthur Fellows award–winning artist Whitfield Lovell is a contemporary African-American artist best known for his works that pay tribute to anonymous African-Americans. Inspired by his archive of photographs, tintypes, and old postcards—all dated between the Emancipation Proclamation and the Civil Rights Movement—Lovell’s works invoke issues of cultural heritage and personal identity as they imaginatively reflect the lives of forgotten Americans. His life-sized charcoal portraits are paired with everyday found objects—including frying pans, spinning wheels, bed frames, clocks, irons, and musical instruments—to reveal the imagined personalities, narratives, and histories of these anonymous figures. Lovell’s works are held in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Brooklyn Museum, among others.

Seen here: Kin LVII (Howl), 2011

Recommended Reading: WHITFIELD LOVELL

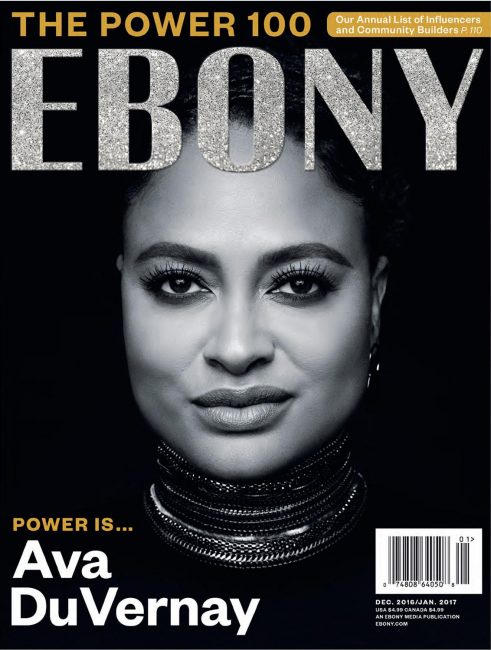

CHANGING DIRECTION

It is no surprise that accolades for the ground-breaking director, producer, and screenwriter Ava DuVernay continue to pile up. A champion for justice—particularly for people of color—her films are beautiful, infuriating, and deeply moving all at once. For her work on 2014’s Selma, a film about the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights, DuVernay became the first Black woman to be nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Director and the first Black female director to have her film nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture. She became the first Black woman to win the directing award at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival for her second feature film Middle of Nowhere, which chronicles a woman’s separation from her incarcerated husband. Her 2016 documentary 13th, centered on race in the United States criminal justice system, won an Emmy for Outstanding Documentary, the BAFTA for Best Documentary, and The Peabody Award. In 2019, DuVernay created, co-wrote, produced, and directed the Netflix series When They See Us, based on the 1989 Central Park jogger case, which was nominated for 16 Emmy Awards—including Outstanding Limited Series—and won the Critics’ Choice Television Award for Best Limited Series.

These are just a handful of the numerous awards DuVernay has either been nominated for or won, making it no surprise that she was named one of Fortune Magazine’s 50 Greatest World Leaders and was included on the annual Time 100 list of the most influential people in the world. Michael T. Martin, director of the Black Film Center/Archive at Indiana University Bloomington, said, “DuVernay is among the vanguard of a new generation of Black filmmakers who are the busily undeterred catalyst for what may very well be a Black film renaissance in the making.” With numerous projects currently in production or set for the future, there is no doubt we’ll be seeing a lot more from this talented, outspoken filmmaker.

Seen here: Covers of Ebony Magazine, July 2017

Recommended Reading: EBONY: COVERING THE FIRST 75 YEARS

A WHOLE NEW BALLGAME

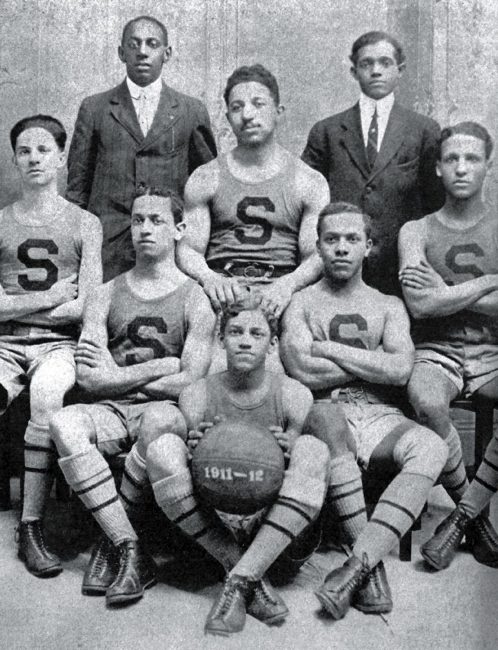

Edwin Henderson was a Black gym teacher credited with introducing basketball to African Americans in public school physical education classes in Washington, D.C. in 1904, 13 years after the sport was invented. Henderson believed that by organizing Black athletics, it would be possible to send more outstanding Black student-athletes to northern white colleges and debunk negative stereotypes of the race. According to Henderson, the new sport was not an immediate hit with his students. “Among Blacks, basketball was at first considered a ‘sissy’ game, as was tennis in the rugged days of football,” he wrote. Yet in 1906, after Henderson co-founded the Inter-Scholastic Athletic Association of Middle Atlantic States, several all-Black basketball teams began to emerge in the Washington, DC area. Soon after, basketball caught on among African Americans in New York City, with these two urban centers serving as the early incubators of the Black game.

The first independent African American basketball team in the history of the sport was the Smart Set Athletic Club of Brooklyn (seen here), organized in 1907. The first inter-city competition between two African American basketball teams took place in 1908 when the Smart Set Athletic Club traveled to Washington, DC to play the Crescent Athletic Club. Brooklyn won the game.

Recommended Reading: CITY/GAME: BASKETBALL IN NEW YORK

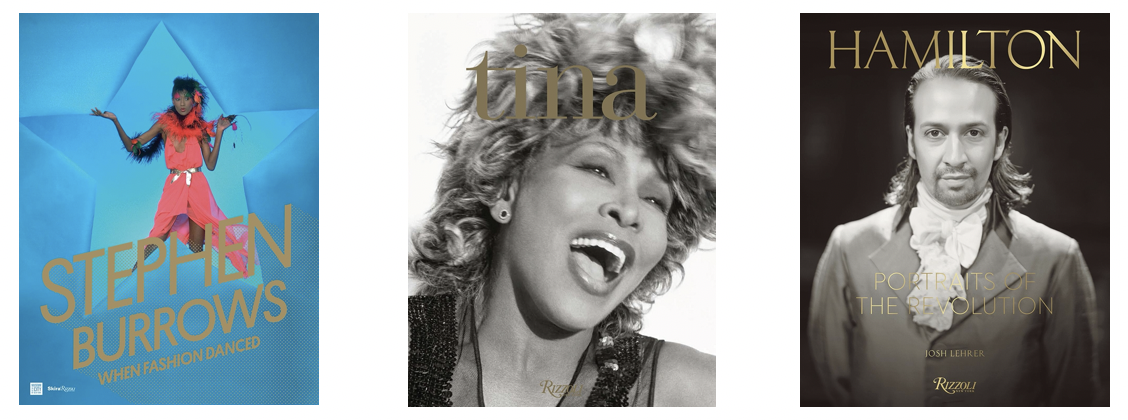

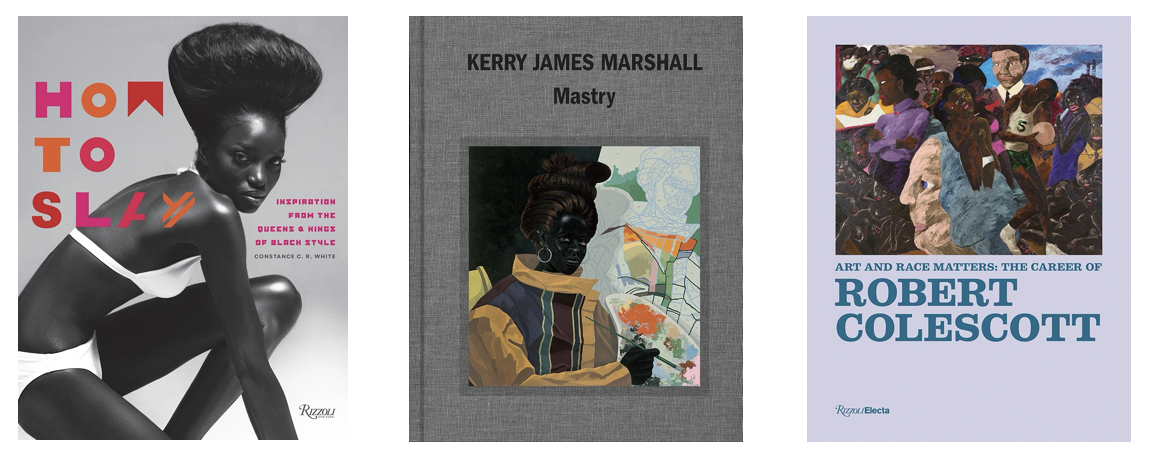

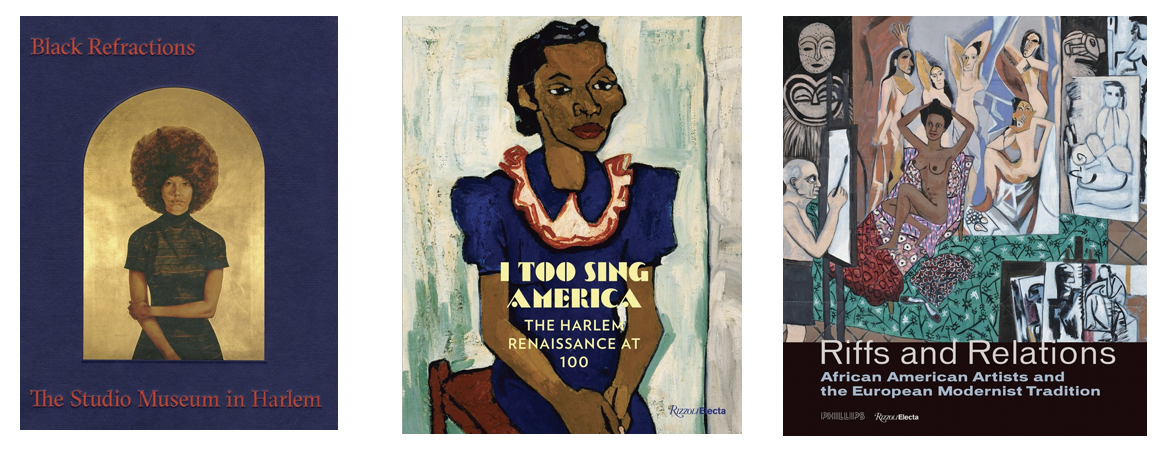

MORE RECOMMENDED READING